Some of the most nerve-wracking films ever made begin with a simple premise: someone knocks on the door of a house in the middle of nowhere, and everything goes wrong from there. Movies like “The Strangers” (2008), “Funny Games” (1997 and 2007), “Ex Machina” (2014), “The Gift” (2015), and “10 Cloverfield Lane” (2016) have all exploited this scenario to tremendous effect, turning isolation from a source of peace into a claustrophobic trap. The stranger-at-the-door setup works because it taps into something primal: the fear that your sanctuary can be breached by someone whose intentions you cannot read.

This subgenre stretches across horror, thriller, and psychological drama, and it has produced some genuinely brilliant work over the past several decades. What makes these films so varied is that the stranger is not always who you expect. Sometimes the visitor is the villain, sometimes the victim, and sometimes the person who was already in the house turns out to be the real threat. This article breaks down the best films built on this premise, examines why the trope works so well, explores how different directors have subverted it, and identifies the patterns that separate a great stranger-arrival film from a forgettable one.

Table of Contents

- Why Do Movies About Strangers Arriving at Remote Houses Work So Well?

- The Best Horror Films Built on the Stranger-at-the-Door Premise

- Thrillers and Dramas That Subvert the Stranger Trope

- How to Pick the Right Stranger-at-a-Remote-House Film for Your Mood

- Common Problems With Stranger-at-a-Remote-House Movies

- International Films That Nail the Remote-House Stranger Concept

- Where the Stranger-at-a-Remote-House Genre Is Headed

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

Why Do Movies About Strangers Arriving at Remote Houses Work So Well?

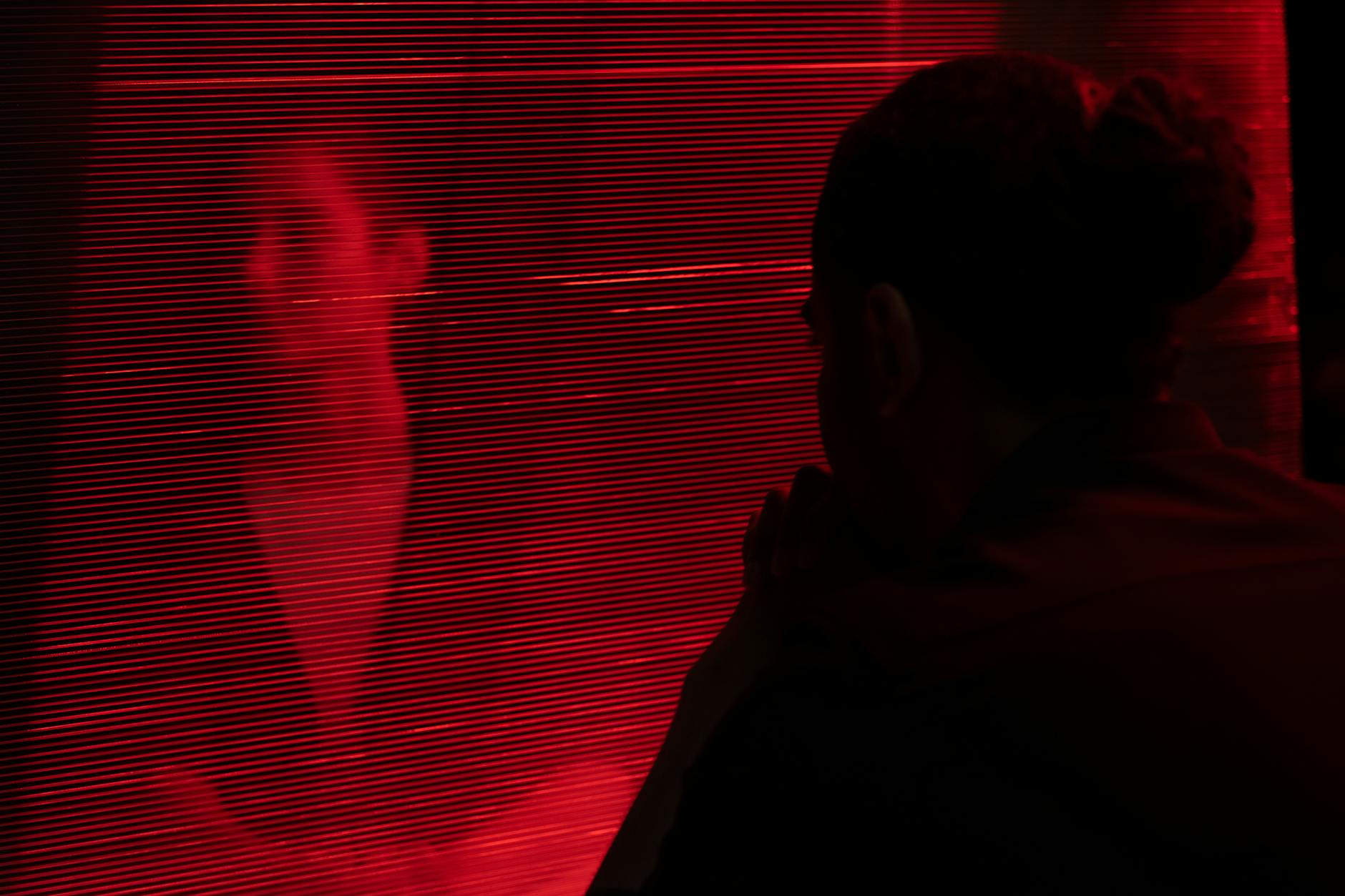

The answer comes down to the elimination of escape routes. In an urban thriller, a character can call the police, run to a neighbor, or disappear into a crowd. A remote house strips all of that away. Cell service is unreliable or nonexistent. The nearest town is miles down a dirt road. Help, if it comes at all, arrives too late. This constraint forces characters into direct confrontation with the stranger, and it forces filmmakers to generate tension from a limited set of tools: architecture, sound, lighting, and performance. There is no cavalry scene to bail out a weak script. The remote setting also functions as a psychological amplifier. In Sam Peckinpah’s “Straw Dogs” (1971), the English countryside cottage that Dustin Hoffman’s character retreats to becomes the site of a siege that tests his capacity for violence.

The house itself, which was supposed to represent a quieter life, becomes inescapable. Compare that to a film like “Hush” (2016), where a deaf writer living alone in the woods must defend herself against a masked man. Director Mike Flanagan uses the protagonist’s disability and the house’s glass walls to create a fishbowl effect. The isolation is not just geographic but sensory. In both cases, the remote house is not merely a backdrop; it is a pressure cooker that the stranger’s arrival seals shut. There is also the matter of trust. When you are far from other people, you are more dependent on whoever is with you. Films like “The Invitation” (2015) exploit this beautifully. The dinner party takes place in a hillside home above Los Angeles, technically urban but functionally remote because the guests have no reason to leave until the host’s true motives surface. Remoteness is as much a state of social isolation as it is a question of geography.

The Best Horror Films Built on the Stranger-at-the-Door Premise

“The Strangers” remains the gold standard for pure home-invasion horror in a remote setting. Bryan Bertino’s film works because it refuses to give reasons. When Liv Tyler’s character asks the masked intruders why they are doing this, the answer is chilling in its simplicity: “Because you were home.” The film strips away motive entirely, which makes the violence feel random and therefore more terrifying. The vacation house setting, with its long gravel driveway and surrounding darkness, ensures that the couple’s screams reach no one. “Funny Games,” both Michael Haneke’s Austrian original and his shot-for-shot American remake, takes a more confrontational approach. Two polite young men arrive at a lakeside vacation home and systematically terrorize the family inside, all while breaking the fourth wall to implicate the audience in their enjoyment of screen violence. The remoteness of the lake house matters, but Haneke is less interested in the setting than in the audience’s complicity.

It is a deeply uncomfortable film, and that is the point. However, if you go in expecting a conventional horror payoff with a triumphant final girl moment, you will be frustrated. Haneke deliberately denies catharsis, which is what makes the film so divisive. Some viewers find it brilliant; others find it insufferably smug. “The Lodge” (2019) deserves mention for the way it combines the stranger-at-a-remote-house framework with gaslighting. A woman snowed in at a remote lodge with her fiancé’s children begins to question her sanity as strange things happen. The film’s slow burn will test the patience of viewers who want faster pacing, but the payoff is genuinely disturbing. The isolation of the lodge makes every odd occurrence feel more menacing because there is simply no rational explanation available and no one else to consult.

Thrillers and Dramas That Subvert the Stranger Trope

Not every film in this space is a horror movie, and some of the most interesting entries use the stranger’s arrival as a catalyst for psychological drama rather than violence. “Ex Machina” fits this mold perfectly. Caleb, a young programmer, is brought to the remote estate of his reclusive CEO boss to evaluate an artificial intelligence housed in a humanoid body. The house is sleek and modern, buried in a landscape of forests and mountains, and there is no way out without the CEO’s helicopter. The stranger here is arguably Ava, the AI, but the film keeps shifting who the real outsider is. By the end, the house that seemed like a tech paradise reveals itself as a prison, and the person who thought he was the evaluator turns out to be the subject. “Parasite” (2019), while set in an urban environment, operates on similar principles. The Kim family infiltrates the Park family’s architecturally stunning home, and the house itself becomes the contested territory.

But there is a stranger already hidden inside, literally living in a secret basement. Bong Joon-ho subverts the trope by making the stranger someone who was there before anyone else arrived. The revelation reframes everything that came before it. “The Lighthouse” (2019) pushes the concept to its extreme. Two lighthouse keepers stranded on a remote island gradually lose their grip on reality. There is no single arrival scene because both men arrive together, but each becomes a stranger to the other as paranoia and isolation erode their identities. Robert Eggers uses the cramped, rain-soaked setting to create a sense of confinement so intense that the ocean itself feels like a wall. It is less a stranger-at-the-door film than a film about how remoteness turns everyone into a stranger.

How to Pick the Right Stranger-at-a-Remote-House Film for Your Mood

The range within this subgenre is enormous, so choosing the right film depends on what kind of experience you want. If you are looking for straightforward, high-tension horror, “The Strangers” or “Hush” will deliver without requiring much emotional investment beyond fear. Both are lean, efficient films that run under 90 minutes and waste no time on subplots. If you want something that lingers psychologically, “Funny Games” or “The Lodge” will sit with you for days, but they demand patience and a tolerance for deliberate pacing. These are films that prioritize dread over jump scares, and they can feel punishing if you are not in the right headspace. “Ex Machina” splits the difference: it is intellectually stimulating, visually gorgeous, and builds to a genuinely shocking conclusion, but it operates more as science fiction than horror.

The tradeoff is that its scares are cerebral rather than visceral. You will not flinch, but you might lose sleep thinking about what the ending implies about consciousness and manipulation. For viewers who want to dig into the art-house end of the spectrum, “The Lighthouse” and Haneke’s work offer rich material but require active engagement. These are not background-viewing films. They reward close attention and punish distraction. The comparison worth making is between a rollercoaster and a chess match: “The Strangers” is the rollercoaster, and “Funny Games” is the chess match. Neither is better, but they serve fundamentally different purposes.

Common Problems With Stranger-at-a-Remote-House Movies

The biggest recurring flaw in this subgenre is the idiot-plot problem: the story only works because the characters make decisions no reasonable person would make. Why does the couple in the vacation house not leave when the first strange knock comes? Why does the protagonist investigate the noise in the basement alone? Skilled filmmakers address this by building in plausible reasons for the characters to stay. In “10 Cloverfield Lane,” the protagonist literally cannot leave because she has been told the air outside is toxic. In “Get Out” (2017), Chris stays at his girlfriend’s remote family estate because leaving would mean accusing his hosts of racism based on a feeling, and the social pressure to be polite overrides his survival instincts. That is sharp, observant writing. A second problem is diminishing returns on the reveal. Many of these films build toward a twist about the stranger’s identity or motive, and if the twist is not earned, the entire film collapses retroactively.

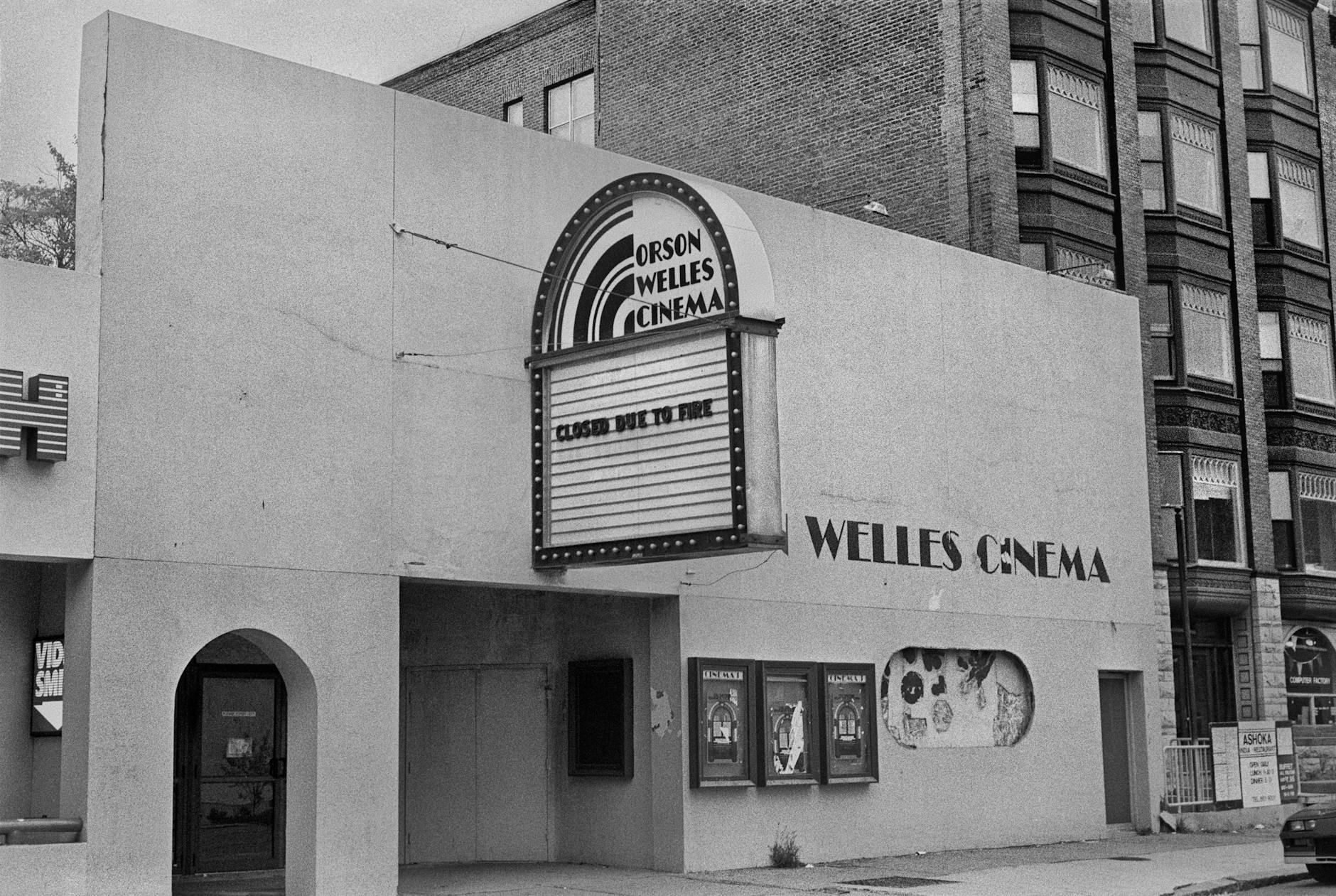

“The Boy” (2016), in which a nanny at a remote English mansion cares for a porcelain doll that the elderly owners treat as their son, has a third-act reveal that many viewers found either delightfully bonkers or completely ridiculous. The line between a great twist and an absurd one is thin, and remoteness alone cannot sell a weak revelation. Filmmakers also sometimes mistake isolation for atmosphere. Putting characters in a cabin does not automatically create tension. Without strong performances and a script that understands why the characters are there and what they stand to lose, the remote setting becomes wallpaper. “Knock at the Cabin” (2023), M. Night Shyamalan’s adaptation of Paul Tremblay’s novel, had the setting and the premise but divided audiences over whether the execution matched the concept. The limitation of the stranger-arrival structure is that it front-loads its hook; everything after the knock has to justify the setup.

International Films That Nail the Remote-House Stranger Concept

Some of the strongest entries come from outside Hollywood. “Goodnight Mommy” (2014), the Austrian original directed by Severin Fiala and Veronika Franz, places twin boys in a modernist house in the Austrian countryside with their mother, whose face is wrapped in bandages after cosmetic surgery. The boys become convinced she is not their real mother. The house is all clean lines and open space, which makes the growing paranoia feel even more disorienting because there is nowhere to hide and nothing to distract from the central question of identity. The American remake (2022) softened the edges considerably, which illustrates a recurring pattern: Hollywood adaptations of these films tend to sand down the ambiguity that made the originals so effective.

“Borgman” (2013), a Dutch film by Alex van Warmerdam, is one of the strangest and most unsettling entries in the subgenre. A disheveled man asks a suburban family if he can take a bath, and from that mundane request, the film spirals into something that defies easy categorization. It is part dark comedy, part parable, part nightmare. The house is not exactly remote, but the family’s affluent bubble functions as its own kind of isolation. The film resists explanation, which is either its greatest strength or its most infuriating quality, depending on your tolerance for ambiguity.

Where the Stranger-at-a-Remote-House Genre Is Headed

The subgenre shows no signs of slowing down, partly because the underlying fear it exploits is only deepening. As more people work remotely, live in rural areas by choice, or retreat from urban density, the anxiety about who might show up at the door remains potent. Recent films have started incorporating technology into the equation: smart home systems that malfunction, security cameras that reveal unwelcome visitors, and connectivity that fails at the worst possible moment. These updates keep the premise fresh without abandoning the core tension.

The most interesting direction may be the continued blurring of who qualifies as the stranger. Early entries in the genre drew clear lines between intruder and victim. Newer films increasingly ask whether the person already in the house might be the more dangerous one, or whether the categories of host and guest, insider and outsider, are as stable as we assume. That ambiguity is what gives the best of these films their staying power. A locked door means nothing if the threat is already inside.

Conclusion

The stranger-at-a-remote-house film endures because it reduces storytelling to its most essential elements: a confined space, a limited cast, and an uninvited presence that disrupts everything. From the visceral terror of “The Strangers” to the intellectual provocation of “Ex Machina,” from Haneke’s audience-implicating cruelty to the genre-defying weirdness of “Borgman,” these films prove that you do not need a massive budget or an elaborate mythology to create something deeply unsettling. You need a house, a stranger, and no way out. If you are looking to explore this subgenre, start with the film that matches your tolerance for intensity.

Work outward from there. The beauty of this category is its range: there is a stranger-at-the-door film for every kind of viewer, from the casual horror fan who wants a good scare on a Friday night to the cinephile who wants to interrogate the politics of space, hospitality, and violence. The door is open. Whether you answer it is up to you.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the scariest stranger-at-a-remote-house movie?

“The Strangers” (2008) consistently ranks as the most purely frightening entry because it offers no motive for the violence and uses long, quiet takes that build unbearable tension. “Funny Games” is arguably more disturbing, but its meta-commentary distances the audience in a way that reduces raw fear in favor of intellectual discomfort.

Are there any stranger-at-a-remote-house movies based on true events?

“The Strangers” was loosely inspired by the Manson family murders and a series of break-ins that occurred in director Bryan Bertino’s neighborhood as a child. “Straw Dogs” was based on Gordon Williams’ novel “The Siege of Trencher’s Farm.” Most films in this subgenre are fictional, though many draw on real anxieties about rural crime and home invasion.

What is the best stranger-at-a-remote-house movie for someone who does not like extreme violence?

“Ex Machina” is the strongest option. It builds its tension through conversation, atmosphere, and ideas rather than graphic violence. “Get Out” is another excellent choice that uses social horror more than physical brutality, though it does have some intense scenes in its final act.

Why do characters in these movies never just leave?

Good films in this subgenre build in plausible reasons: the car will not start, the roads are impassable, the protagonist does not realize the danger until it is too late, or social pressure makes leaving feel like an overreaction. When films fail to address this question convincingly, it is usually the script’s weakest point.

Does “The Shining” count as a stranger-at-a-remote-house movie?

It shares DNA with the subgenre but inverts it. The Torrance family are the newcomers to the Overlook Hotel, and the “strangers” are the ghosts already there. It is more accurately a haunted-place film, but its use of isolation and confinement clearly influenced many stranger-at-the-door movies that followed.